[The audio version of this article is available on the Pondering Purple podcast. Click HERE to listen or find it on your preferred podcast platform.]

A couple years ago, I wrote an open letter to victims of abuse that garnered some significant attention. It was based on my own experiences as a child and teenager—and it recounted the manipulation, dehumanization, and molestation that scarred me. If you have been victimized or know someone who was, I encourage you to access that piece in written or audio format.

This is a follow-up to that article, intended to provide parents with concrete steps for preventing, recognizing, and responding to abuse. These recommendations would apply to any family raising children in this broken world.

But we must acknowledge that there is something unique about MKs that may put them at greater risk of having their abuse go unreported and unaddressed.

In part, it’s the pressure they feel to shield their parents from their suffering, to protect their image on the field and at home, and to preserve the important work in which they’re engaged.

These preoccupations can inhibit reporting, which in turn can delay or deny them the help abused children desperately need.

A lack of holistic understanding about the pervasive presence and manipulative methods of abusers might further prevent missionary parents from taking adequate precautions for the safety of their children.

The busyness so common among adults in ministry settings can also prohibit recognizing red flags and noticing signs that all is not well.

We know that sexual abuse and assault are a global plague. The statistics are horrifically high around the world and rising year to year. And in cultures where women and children are viewed as subservient to the will and impulses of men, abuse is likely vastly underestimated.

The forms and methods of abuse are broader today than they were in the past—with some predators now finding their prey online and harming them in virtual ways—and children growing up in ministry are just as vulnerable to sexual harm as their non-ministry peers are.

I won’t describe for you the stories I’ve heard—they are too raw and disturbing to be recounted as media content—but I can tell you that there are fewer and fewer safe places for children and teens of any gender to grow up. And the assailants often come from inside as well as outside the ministry community.

As people called by God to embody his love and protection for the young and helpless, we must get better at preventing, recognizing, and responding to abuse.

There are some steps we can take—and messages we can convey—that will at least reduce the vulnerabilities of potential victims, lessen the opportunities for aggressors to strike, and offer thoughtful solace and assistance to those who have been harmed.

It goes without saying that there is no such thing as 100% prevention. We live in a cruel world, surrounded by broken and brutal humans, and the total isolation that could create more safety is neither healthy nor entirely possible.

So—what can parents and other adults of influence in the lives of MKs do? The suggestions I’ll make here are merely entry points into this conversation, and I encourage you to deepen your understanding and sharpen your strategies through further study and implementation. If you have thoughts and resources of your own to contribute to this overview, please use the comments section at the bottom of this post to share them.

1. Acknowledge that we live in a twisted world

Horrible things can happen even to children whose parents work in ministry. But we’ve anesthetized our caution with delusional statements like “The safest place is the center of God’s will” or “Nothing bad can happen to us because we’re serving God.”

The illusion of safety can be a dangerous thing. It leaves us unwatchful and unguarded. Blind and vulnerable.

Please hear me: if you’re burying your head in the sand about the risk of sexual violence, you’re burying your child’s head too—and the consequences could be tragic. Open your children’s eyes the dangers around them, in an age-appropriate way, and broaden their understanding as their awareness increases.

The saying holds true: Forewarned is forearmed.

Teach your children that caution is good, that instincts are valuable, and that some people, even “nice” ones, can have a dark and destructive side.

They’ll need to trust their gut and their interpretation of events if they’re going to learn to protect themselves, and the confidence to do that begins with the knowledge that there are unsafe places and people in this world.

2. Teach your children a clear definition of what sexual abuse is

Because of their complex identity, this definition should be a framing of inappropriate words and touch that preempts culture and context—the kind of statement that says, “No matter which country you’re in, if anyone treats you this way it is not okay, and telling us about it is important and right.”

Some of our MKs growing up in cultures where gender roles, sexuality, and bodily autonomy are viewed differently may not even realize that what they’re experiencing is abuse.

This was certainly the case for me. Though my instincts told me that what friends and strangers had done to me crossed some kind of moral line, the normalization of such treatment in the environment in which I lived suggested that I might be overreacting. So I said nothing. And I declared myself fragile and mistaken when the memories came back to haunt me.

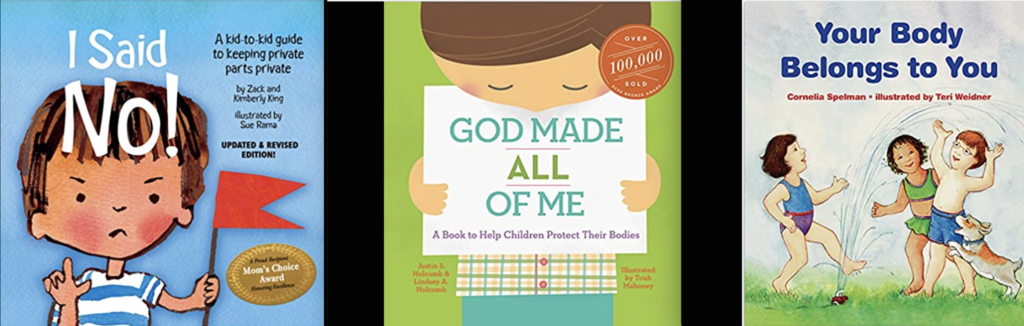

3. Make sure your children know that their bodies are sacred

There’s something that can feel like “common ownership” in the lives of MKs. It comes from the very public way our families live and report on the work we do. Think of the newsletters we write, the invasive questions we routinely answer, and the right we give people outside our family to observe and evaluate us.

There can certainly be good aspects to this uniquely “missionary-world” trait (accountability among them), but it can also send a confusing message to MKs.

Children growing up in a context in which their every ministry project, family trip, and budget line item are common knowledge must also understand that there are things they’re allowed to consider private.

Their bodies—their personal space and chosen connections—belong to only them. They need to know that no one else, even in their tight-knit missionary community, has the right to touch them without consent.

Their bodies are not common property, and it is not only okay but good for them to report back to mom and dad about anyone who infringes on their boundaries.

That may sound unnecessarily stringent. But I can tell you that my childhood innocence might have been protected if I’d been given the simple message that my physical body was precious. It was mine to protect, and no one had implicit access to it.

4. Foster honest communication on tough topics

It’s hard to speak of sexual abuse if you don’t have safe, familiar words to use for reproductive organs and improper behavior. So I encourage you to broaden your family’s vocabulary to include clear names for body parts. And talk openly about the kind of touching that is never okay.

Give children words that will facilitate reporting back to you if ever the need arises, as well as a strongly-stated permission to speak of sexual things whenever they need to—even if it’s uncomfortable.

Equally importantly, make it clear to your children that you will always—always—want to know if someone (friend or stranger) has done or said anything questionable to them. Even if it just might have been inappropriate in their minds, make sure your children know that you want to hear about that too and that you would never blame them for what they reveal to you.

5. Prove to your children that they matter the most

MKs will sometimes sacrifice their own needs to ensure that their parents’ ministry isn’t harmed, because they’re convinced that their own welfare is less important than the work in which their parents are involved.

An adult MK recently wrote this to me:

“There was nothing in the way my parents treated me that made me feel I was in any way more important than making inroads with the neighbors and building the church annex. Any need I had felt like an interruption or a distraction from what they really wanted to do. So I kept it to myself. We were clearly in Africa for others, not for me.”

If that sometimes-only-implied message keeps a child from seeking help at the first hint of abuse, the consequences can be (and have been) devastating.

Your children need to grow up with the firm conviction that they are more important to you than your image, your obligations, and your deadlines.

Practice conscious conversation, the kind of interaction in which they see you laying aside your tasks and preoccupations in order to concentrate solely on your children. If they see you consistently, gladly interrupting your work to focus on them, they’ll be more likely to interrupt again if they have something important to report.

6. Believe them

When your children bring something suspicious to your attention, do not use phrases that make it sound like you’re doubting them. “Are you really sure?” or “He may not have meant it that way.”

Nothing will shut down a victim of abuse faster than being doubted or dismissed.

If you’ve never been submitted to the multi-faceted trauma of abuse, you can’t possibly understand the courage it takes to report it. So one word of disbelief—even a dubious facial expression—can cause the victim to shut up and never speak of it again.

Instead, gently ask questions. Gather as many details as he/she is willing to reveal about what happened.

Sometimes, the initial “purging” that accompanies a revelation will be the most complete story that victim will ever offer, as if a dam has burst and he/she can’t stem the retelling.

Later on, the victim might be much more guarded in the revelations he/she makes, at least for a while.

So make of that first conversation a supportive, inquisitive, and non-judgmental interaction in which important details about the allegations can be expressed. Make sure you give the child the time, the affirmation, and the freedom they need to say everything he/she wants to say in that moment. Then validate the strength and courage they’ve exhibited by putting words to their trauma.

Eventually, the victim will need to see your own anger and grief as you all process together. It is good and healthy for that to happen. But in that initial conversation, though you should be genuine in reflecting back to them the seriousness and pain of what they’re revealing, make sure your own emotions don’t overwhelm theirs and hinder their ability to fully disclose what needs to be spoken.

7. Be willing to sacrifice your world to save your children

There are several instances in which I’ve witnessed parents who knew that something horrible had happened refuse to take action because it might make things “complicated”—damage their ministry, harm important relationships, be misunderstood by supporting churches, or require that they stop serving God to care for their injured family member. (Not realizing, perhaps, that rescuing their children is in fact serving God.)

In some cases, I’ve seen administrators to whom molestation was reported minimize the assault and deny its impact on young souls. I’ve seen heads of missions labeling child-abuse reports as “interpersonal conflict” and suggesting team building exercises to reconcile the adults involved, rather than providing emergency help and long-term care for the children who found the courage to report the harm done to them.

If your child has been abused, report it to those who can do something about it, no matter the cost. And if those people don’t act, move up the chain of authority until someone takes steps to hold the perpetrator accountable and to prevent further abuse. Enlist others you trust to help you and advocate for you. And go outside your organization if you need to.

And while you’re fighting to bring perpetrators to justice and prevent others from becoming victims, don’t lose sight of your children. Move them to safety, even if it means leaving your home and field of ministry. Comfort them. Validate their pain.

Show them that they are important enough to God and you that you will do everything you can to help heal them, regardless of the inconveniences and losses it may demand.

8. Seek help

Surviving child abuse is never a do-it-yourself project.

If lasting and complete healing is to be reached, the involvement of a therapist trained in counseling victims and their families is absolutely essential.

Sexual assault is trauma—molestation is trauma—and there are clinical approaches to treating PTSD that can be restorative and transformative. So avail yourself of qualified help, and if your funding doesn’t allow it, get creative in seeking financial assistance.

Be relentless in your family’s pursuit of wholeness.

Child abuse is a crime that can hobble generations in myriad ways.

Let nothing come between your child and the healing God desires for all of you.

Abuse is not the end.

Helen Keller wrote, “Although the world is full of suffering, it is also full of overcoming it.”

I’m here to tell you that statement is true. There is hope. There is healing. There is wholeness beyond these devastating shadowlands. And it is never too late to seek counsel and treatment.

After the world-shattering abuse of my youth, I received insufficient help that only papered over my pain. But I did eventually find the assistance I needed, and—as I was able to define and explore my trauma as an adult—I found my footing again in a way I thought would never be possible.

So if you’re an MK whose sexual assault still feels like a bleeding injury, please—do not despair. Seek out the counsel you need now. Fight for your wellness. And if you don’t have to strength to advocate for yourself at this point, reach out to me, and I’ll do all I can to help you find the assistance you deserve.

You are valuable. You are worthy. And this is not the end of your story.

And if you’re a missionary parent whose child has been harmed, there are all kinds of resources available to you. The Child Safety and Protection Network is a good place to start. There may be qualified professionals within your mission who can help you too. And beyond that, there’s a large network of therapists devoted to working with missionary families that can be accessed even virtually from most places in the world.

Please reach out to me if you can’t find the assistance you need, and I’ll try to facilitate connections with someone who can guide you.

Of this I am sure: God stands and fights with us as we endure the pain of life in a broken world.

He whispers wisdom for prevention of abuse, imbues insight for recognition of abuse, and promises strength for our response to abuse.

He is mighty, loving, and just. And his beautiful heart will ever bend toward us.

Please join the conversation!

-

- Contribute your thoughts in the comments section below

- Use the social media links to Like and Share this article

- Many of these articles are now available in podcast form. Simply search for “Pondering Purple” on your usual pod platforms, or click this link to be taken to its host page

- To subscribe to this blog, email michelesblog@gmail.com and write “subscribe” in the subject line

- Pick up Of Stillness and Storm (my novel about a missionary calling gone awry) on Amazon