[The audio version of this article is also available. Listen to it on the Pondering Purple podcast by clicking HERE.]

As I’ve spoken with Missionaries’ Kids (MKs) of all ages over the past thirty years, a few commonalities have emerged—traits shared across locations and demographics within the cross-cultural world of missions. One of the most prevalent of those is what I call The Tyranny of Shoulds.

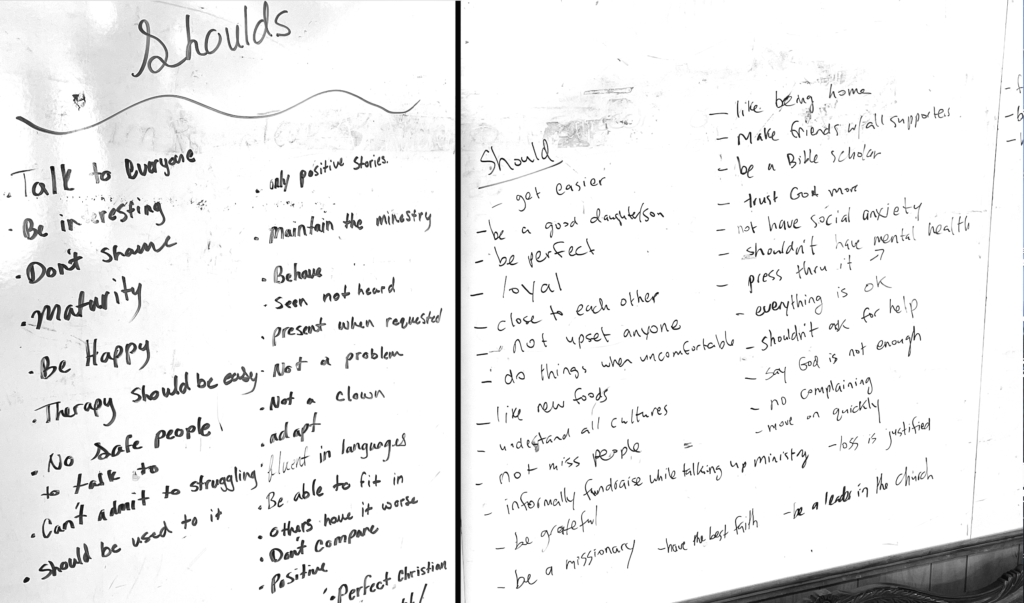

[Click on above photo to read a partial list compiled by young-adult MKs in 2022.]

[Click on above photo to read a partial list compiled by young-adult MKs in 2022.]

Before I get into the crux of the issue, it’s important to state that this is not an MK-specific phenomenon. Children raised in other intensely religious contexts (like pastors’ kids and prominent-believer’s kids) might experience them too. So as I refer to “MKs” in this article, feel free to substitute your family name for the acronym. It may feel more pertinent to you that way.

Also, though I refer to family rules and guidelines that are based on biblical principles in this piece, I am conscious that some of you who still deal with residual Shoulds may no longer live by the same value system that was the basis for the expectations that shaped your childhood. So, as I speak of God and faith, please substitute the source and nature of the values you live by today—as even non-biblical pressures can warp our worldview and self-assessment.

I want to begin by noting this:

A majority of MKs—despite the difficulties sometimes associated with growing up between worlds in the high-pressure context of ministry—still count it as a hugely positive thing.

In a survey of over 1,000 MKs (see HERE) I conducted back in 2011, 60% said they “wouldn’t trade it for the world” and another 30% described it as “mostly positive.” That’s 90% who have a favorable view of being Missionaries’ Kids.

MKs are certainly aware of the Wonderful of their lives—I love that about them! But that doesn’t mean there aren’t more painful aspects too. And there are so many members of “my tribe” who experience the Tyranny of Shoulds in a debilitating way that I believe addressing them is essential—not out of a morbid desire to dig around in the dark, but out of a commitment to unpack one of the major challenges inherent to being an MK, so more of us can begin to thrive in the light.

You might wonder how Shoulds are different from regular family rules and guidelines.

Rules and guidelines assume that growth will happen through practice, that grace will be needed for the ups and downs of the process and that second chances will be extended to children who are prone, as we all are, to learning through trial and error. With rules and guidelines, there’s a tacit understanding of apprenticeship.

The subtext is: “These rules represent God’s best for you. They will mature you, protect you, equip you to be a good and responsible human. They will enhance your life. So keep trying if you fail—the benefits are worth the effort. And none of these are deal-breakers when it comes to the love and acceptance we extend to you.”

On the other hand, oppressive Shoulds have no such nuance.

Their subtext is: “These are the orders we are anchoring to you as an inflexible expectation. Failure to live up to them will leave an undilutable stain on you. So let these Shoulds seep into your subconscious and motivate your every move, because you don’t get to be frail or confused or lacking self-control. Fail once and you’re tarnished forever in the eyes of anyone who matters, your Maker included.”

Can you see the different weights of those two sets of subtexts?

One expects growing pains along the way to maturity. The other rejects developmental growth and demands instant perfection instead.

One leaves space for the development of autonomous thinking that sees the compelling grace of family values. The other demands adherence without any ownership.

There was a look my dad would give me. He didn’t have to say anything. He just gave me that look and I knew I had done or said something I should be ashamed of. Most of the time, I didn’t even know what it was, but I remember the way his hard stare would hit the pit of my stomach.

— Joe —I was raised more by Shouldn’ts than Shoulds, both enforced by shame. […] The Shouldn’ts verbalized to me as a child and teen were: You shouldn’t wear black, which equaled death and rebellion. […] You shouldn’t sing in public places and draw attention or study what you enjoy in life (for me, art and music), but study what is logical and prestigious according to your parents’ values. You also shouldn’t acknowledge or trust your emotions, nor should you pursue happiness or wealth of any kind other than the invisible spiritual wealth of someday in heaven.

— Rebekka —My family had many shoulds, both spoken and unspoken…things like – you should rejoice in suffering – you should think of others and not yourself – you should represent Jesus well – you should be happy about everything – you should be submissive – you should love God – you should always work hard/do your best/be perfect.

— Hannah —

Joe is thirty-something, Rebekka is in her fifties and Hannah is twenty-six. They may come from different different decades, but they’ve all experienced Shoulds that have felt toxic and exhausting. Some MKs learn to manage them early in life, often with the help of parents who are aware of the pressures. Others, perhaps because of personality types or an independent spirit, are able to let them go as they grow into their autonomy. Yet others might still hear the Shoulds speaking from their subconscious, but they recognize them as irrational and have learned to quiet them.

But some MKs—dare I say, many—are still tormented not only by the demands of perfection that shaped them, but also by the weight of their failure to live up to them.

If you ask MKs where the Shoulds came from, they might be hard-pressed to give you a clear answer. They might say that it’s the sending mission, their partner churches, their supporters, the missionary community on the field, their relatives back “home,” their own family…or a combination of all of those. Many won’t be able to point to a clear articulation of the outrageous and unrealistic expectations. They just knew they were there, looming over them.

Most of these [Shoulds] were conveyed through either actual spoken words, or through punishments that were given when we failed. Some were modeled by my parents and other adults around me, in their actions and attitudes, and I just “caught” them.

— Hannah —There is a “should” in a Sunday School Teacher saying, “Today we have a missionary child in our class – we will ask her all the lesson questions because I am sure she knows the answers.”

— Elizabeth —One of the hidden “rules” that many MKs learn intuitively is to never do anything that could potentially undermine their parent’s ministry.

— Mark —The expectations put on me from earliest memory felt like a straight-jacket. They just kept droning in the back of my mind until I became my own judge, jury and executioner.

— Rowan —

As Rowan indicates, we often end up inflicting the oppressive pressures on ourselves. The external tyranny becomes an internal tyranny before we even realize it, because we feel so inordinately responsible, as MKs, to protect our parents, their ministry and God’s “reputation.”

I recently sent out an informal survey to adult MKs, asking them to identify the most intense Shoulds they experienced in their growing-up years—and might still even subconsciously experience as adults. In order of decreasing percentage, the top five were:

- I should behave well at all times

- I should be exemplary in every way

- I should not cause my parents more stress (“I should not bother my parents with my struggles” was also among the top ten)

- I should have mature faith

- I should serve others until I have nothing left to give

Read those five Shoulds again and ask yourself what kind of pressure they mean to a primary school pupil who is struggling with life in a fishbowl, in a place where her family is seen as the embodiment of Christ. What they might mean to the ten-year-old whose family is visiting financial partners and churches, weary from all the travel, but aware that all eyes are on him. Or to the twelve-year-old whose family has just moved for the fourth time, who feels uprooted, lost, insecure and buzzing with the kind of stress that makes her want to scream and lash out.

Imagine what those five Shoulds might feel like to the teenager whose anxiety is beginning to manifest in visible ways. Or whose behind-closed-doors family life is the antithesis of what it expresses publicly. Or who has witnessed disease or famine, or been abused, and doesn’t know what to do with all the trauma. Or who—for heaven’s sake—is just trying to make the fraught transition from childhood to adulthood, under complex circumstances, but is convinced that one wrong move witnessed by others will bring a deluge of shame, reproach and punishment he might not be able to withstand.

Imagine trying to climb the mountain of life—with its treacherous slopes and blind corners—with a stack of unwanted boulders heaped on your shoulders and the certainty that a condemning world is watching your every step and stumble.

The five Shoulds that topped the survey are significant in what they convey.

- I should behave well at all times. Other kids can be less than perfect, but because I’m an MK, I cannot. I need to be consistently above reproach. If somebody sees me throwing a tantrum or talking back to my parents or not telling the truth or being mean to another kid or doing poorly in math class or being depressed, I have failed. I cannot do any of that at any time because it might bring shame to my family, their mission, and God himself.

- I should be exemplary in every way. Not only should I behave well at all times, but I should be the person people point to and say, “See her? She’s the kind of person we want our kids to be. She’s so mature, so respectful, so adaptable, so competent, so positive, so servant-hearted.” So I don’t just need to be good. I need to be extraordinary—held up as an example for others to follow. It comes with the MK label, and if I fall short of the expectations, as unrealistic as they may be, I could bring shame—once again—to my family, their mission, and God himself.

- I should not cause my parents more stress. They’re already under so much pressure. I can tell they’re exhausted and overwhelmed. If I tell them that I’m struggling or if I misbehave and take too much of their time and attention, it will interrupt their important work. I need to be a good little soldier and take care of myself, because they’re doing such important things and I shouldn’t interrupt them. I shouldn’t express my struggles and hurts to them, because taking their eyes off their ministry might bring shame to my family, their mission, and God himself.

- I should have a mature faith. I know I’m only six. I know I’m only nine. I know I’m only fifteen. But my family’s work for God is what defines us. How can they bring Jesus to the people they serve and have a child t home with a fledgling faith—or worse, an uncertain faith? I need to talk about Jesus confidently with others, even if it isn’t my personality type. I need to want to read my Bible and to want to have daily devotions. I need to know more about God and the Bible than any other kids my age because I’m an MK, and if I don’t excel in everything including my faith…I might bring shame to my family, their mission, and God himself.

- I should serve others until I have nothing left to give. God doesn’t call us to have healthy boundaries that protect us, our relationships and our faith. I’ve seen it in nearly every missionary I’ve met—we’re called to pour out every ounce of what we have to give, whatever the cost. I should stuff down any impulse to rest or recharge because sacrifice is always good and laudable. Whether I’m a kid or an adult, I am here to invest myself limitlessly in others, and anything less than that might bring shame on my family, their mission, and God.

As nearly-universal as an MK’s love for growing up between worlds might be, so are the recognized and unrecognized Shoulds that anchor themselves to our self-awareness and worldview in both benign and toxic ways.

We must do better at recognizing and contradicting them, lest they become a lifelong influence on how we view ourselves, our families, our faith and our Savior.

What can we do to counteract the power of Shoulds?

A word for MKs still living under the tyranny:

It can feel uncomfortable or wrong to give ourselves the permissions we need—to counteract the Shoulds with statements that affirm our worthiness of love and respect, and our capacity for autonomous thinking and self-regulating. (The latter of which may sometimes require some external influence—but one we choose, not one that is imposed on us with a load of guilt attached to it.) To be honest, I still occasionally catch myself feeling broken for not living up to the irrational expectations that gripped my childhood. I need to repeat to myself over and over the unassailable truths I now know to be of God:

- I am a precious human being, created by God, imperfect, still-learning and worthy of his love

- My value is not dependent on behavior or performance

- My self-esteem does not hinge on the approval of others

- I will feel no guilt for doubt or non-conformity, but seek honest answers as I embrace the uniqueness God created in me

- I will seek to live out Good values and purposes, knowing that my failures are not deal-breakers and my flawed humanness is never the final straw

- I will try again and again when I stumble, because growth is a continuum and grace is God’s way

- I will reject the straight-jacket of irrational, performative Shoulds and look instead to make right choices and love well

- One more time for those in the back: I am a precious human being, created by God, imperfect, still-learning and worthy of his love

Today I often use the phrase “I get to” and am growing in my freedom to say “I would love to…” I am learning to live from knowing I am already accepted. I am learning to release more and more shoulds and shouldn’ts, and to embrace freedom and joy, even when I no longer impress everyone as acceptable.

— Rebekka —

A word for those who are parenting MKs:

These are the suggestions of adult MKs who have looked back on their growing-up years and formulated countermeasures to the pressures that crushed them.

Firstly, we need to out-message the Shoulds. They are so intense, insistent and manipulative that contradicting them will require intentional, reiterated and clearly-spelled-out messaging about what the family’s rules and guidelines really mean. Nuances matter—and they may look like this:

- These are our family values and we’ll work on them together

- We want you to do your best to abide by them

- This is about fostering growth and goodness, not about impressing our neighbors

- We know it will be hard—it’s hard for us too—but it’s worth it because reaching for what is right will grow you into a strong, responsible, kind, honest and loving person

- You’ll probably make mistakes along the way and that’s to be expected—keep trying and you’ll keep growing

- Your failures will not change our love for you—you don’t have to do anything to earn it

- God isn’t going to walk away from you either, because he knows we all mess up and he loves us more than we can imagine, even when we make wrong choices

- And FYI, as our child you are more important to us than any other person on this planet

This kind of message needs to be conveyed over and over, consistently, clearly, verbally and non-verbally. It needs to be demonstrated as much as stated. The Shoulds sink into our sense of self and murmur constantly. It will take a concerted, long-term effort to keep them from gaining traction in children’s view of themselves and in what they expect from those who care for them.

Secondly, we need to consider changing our vocabulary. In his excellent book, I Have to be Perfect, Timothy L. Sandford suggests eliminating the word Should from our conversations with children—and from the way they themselves express their family’s values. Shoulds are demands that impose bruising expectations and the fear of failure on young minds. Other words, like “can,” “if” and “let’s” might nurture connection while delineating benchmarks and allowing for collaborative effort.

The family rules and guidelines are still there. But the expectations are couched in thoughtful guidance, encouragement and reflection. There is no hint of “don’t you dare bring shame on our family.”

Thirdly, be aware of the Six Permissions Most MKs Need and regularly verbalize them. I’ve written a full article on this topic HERE, but will summarize the three most pertinent points below in the context of Shoulds.

- Given permission to be kids, MKs will understand that full adult maturity isn’t expected of them and that the guidelines they’re encouraged to live up to have “formation” built into them: a gradual apprenticeship that doesn’t demand instant perfection. Permission to be kids assures children that they will be nurtured, protected, discipled and taught as they grow into adulthood.

- Permission to fail assures children that they will get do-overs, that maturing is a continuous process, and that even repeated non-observance will not sever the relationship they have with their parents or God. Permission to fail removes the toxic demands of Shoulds by affirming family expectations while simultaneously extending understanding, mercy and grace.

- The Should-imposed stigma of a weak or underdeveloped faith will be assuaged by permission to doubt. It will declare to children growing up in the intense world of ministry—and often privy to behind-the-scenes dysfunction—that God knows we’re all a work in progress. They will be reassured about the resiliency of his love and its relationship to our personhood, not our behavior. Permission to doubt (or be unsure or be less than a world-class theologian at age ten) will preserve a child’s journey toward faith by allowing for stumbles and sidetracks. It has the power to change his/her view of God from a domineering and demanding tyrant to a love-motivated teacher whose devotion is not swayed by immaturity or failure.

The debilitating power of spoken and unspoken Shoulds in the world of Missionaries’ Kids must not be ignored. It can deeply affect self-esteem, relationships, mental health and spirituality. A vigilant awareness of the toxic messaging and a commitment to counteracting it with clearly-spoken truth may not completely eliminate the pressures a majority of Missionaries’ Kids feel, but it can blunt the damaging impact of the Tyranny of Shoulds.

Please join the conversation!

-

- Contribute your thoughts in the comments section below

- Use the social media links to Like and Share this article

- Many of these articles are now available in podcast form. Simply search for “Pondering Purple” on your usual pod platforms, or click this link to be taken to its host page

- To subscribe to this blog, email michelesblog@gmail.com and write “subscribe” in the subject line

- Pick up Of Stillness and Storm (my novel about a missionary calling gone awry) on Amazon