I’m a student again. When I finished my course work at Wheaton back in 1989, I swore (SWORE!) that I would never enter a classroom again.

Imagine my surprise, last month, to find myself preparing for my first class in over 20 years. I walked with feigned confidence into the classroom holding 30 or so young grad students. They mostly knew each other from previous courses together, so no one paid much attention to the much-older woman fielding hot-flashes in the back corner. Right up until my pen flicked out of my tense fingers and skittered loudly two desks down before falling to the floor. It happened twice. And every time a younger classmate returned the pen to me with something that looked like condolences on his face.

For two hours every Thursday, I return to the Billy Graham Center for an interactive class on “Care and Counsel in Ministry” that has sharpened my thinking and acutized my calling. “Acutized” is a made-up word. I can do that now that I’m involved in higher education!

My student career hasn’t always been as fulfilling or entertaining as it is today. If you know me well or have heard me speak on MK topics, you’re aware that my introduction to learning was rocky. I was insecure and fragile when I began first grade in the French school system—a system North Americans would rightfully call abusive. I have a few good memories of those initial years of schooling: the substitute teacher who brought his guitar to class and sang us French folk classics by Yves Duteil or George Brassens. Watching tadpoles turn into frogs in jars at the front of the class. Going on a field trip to the nearby woods to pick Lilies of the Valley for the first of May. Traveling to Paris in 7th grade to watch the very first version of Les Misérables—minus the elaborate sets, rotating stage and expanded storyline of today’s Broadway show. Playing hop-scotch. “Un-deux-trois soleil.” Jump-rope. And a game in which a person would perform elaborate tricks with an elastic circle stretched between two friends.

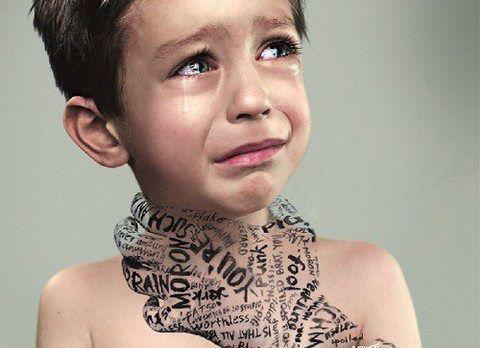

But the bad memories—they far outnumber the good. Teachers who would pull my ear until the earlobe bled. Who would tell me how stupid I was and that I’d never amount to anything. Who pinched a nerve in my shoulder that would make my arm go numb. Who stood me at the front of the class with a dunce cap on my head and instructed my peers to mock me into…what? Into brilliance? The French system believed then (and still somewhat does now) that humiliation and pain are a catalyst for achievement. I beg to differ.

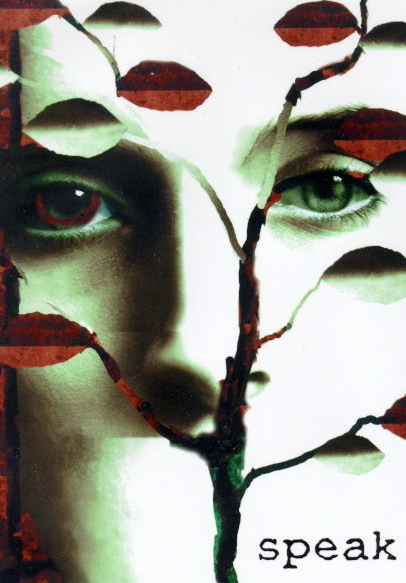

Today, as I speak about my experiences in various venues, I’m frequently asked why I didn’t tell my parents about the physical and verbal abuse I suffered at the hands of educators who were supposed to be benevolent and trustworthy. My answer is simple: because I thought it was normal. Though the verbal taunts may have been more easily aimed at the shy “Américaine” in the back row, no one in my class was spared. We were all treated like stupid nuisances who served no other purpose than to exasperate impatient teachers. It was normal. Just like being chased back and forth down the street, terrified and sobbing, by older boys on bicycles was normal. Being propositioned by old, foul-breathed men was normal.

Normal was frightening and maiming, but not worth reporting.

I wonder how many other MKs, even today, are going through experiences at school and at home that feel utterly wrong but are considered normal—because they are so common. I’ve seen it in my former students at BFA. Girls who were raised in Muslim countries where a woman highest calling is to be a man’s possession. Boys raised in neighborhoods where group violence promised inclusion. Children whose young lives were bruised or branded by aberrations they assumed were “normal” because they were so widespread and tolerated.

If you’re an MK who has endured something that has hurt you in any way, I urge you to speak of it to someone today. Even if you get the impression that everyone around you suffered the same fate. Nazi Germany proved that an injustice’s scale doesn’t lessen its wrongness or its impact on individuals. If you have experienced physical, emotional or sexual harm without speaking of it to anyone, please—please—find someone you trust and speak your story. There is a freedom you can’t imagine that comes from revealing past grievances, no matter how distant they are. It will release your present from the anchors of your past. And there is healing to be found by exploring the painful memories and their scars with someone who can help you toward wholeness. (If you have no one to speak to, please let me know so I can help you to find someone who will listen and help… My email.)

And missionary parents—as you seek to know and understand your children, I urge you to realize that some of what is “normal” in your part of the world might leave indelible marks on your children’s lives. It may be so ordinary that your children don’t want to bother you with admissions of pain. I’ve seen enough MKs devastated by “normal” that I urge you to ask pointed and persistent questions of your children. Give them the opportunity I never got to voice the reality of their daily challenges and struggles. Remove from their shoulders the burden of whitewashing their experiences in order to make your lives easier. Nurture a relationship in which honest communication trumps blissful ignorance. And if you perceive that something isn’t right, even without an admission on their part, take measures to find out what might be causing the changes you see in them. Pursue and address it. Let your children know that if “normal” hurts them, you’ll do all you can to spare them from further harm. Make sure they understand that nothing is more important to you than their safety and welfare.

When I first arrived at BFA, fresh out of the French school system, I doubted that any of my teachers were as kind as they appeared to be. I lived with the expectation that adults in authority would invariably cause me to suffer. It took years to prove the assumption wrong. I’m still working on some of the other faulty conclusions I drew from growing up in a much different culture. But now, as I head to class at the Billy Graham Center each Thursday, it’s with two unflagging certainties:

- How blessed I am to be involved in a ministry that promotes understanding, prevention and healing.

- How glad I am that in the context of Wheaton College, my earlobes are safe, my arm is un-numb and there isn’t a dunce cap to be found.

To donate to this important ministry, please click HERE.

Make sure you specify that it’s for Michele Phoenix’s ministry.

michele

From CS, on Facebook: “It’s good to hear someone else verbalize things I can hardly put into words. I thought a lot about how I had learned things growing up when I went into education in University. I realized then how the education system here is vastly different and consequently why the culture here is soooo different than what I grew up in. Though I didn’t agree with educational methods in France, I realize why I teach a certain way and do certain things in class (things that motivated me to learn because of my upbringing that just don’t seem to motivate others) and I still have a lot to learn…”

Jennifer2838

I had an experience like this with my oldest daughter when she told us that when she was a little girl a neighbor lady had locked her in a room (just to “tease” her — the people where we live are very cruel in the way they tease children). On the whole, her MK experience was very positive: like you she returned to the boarding school she graduated from to teach, and loves coming “home” to our country for holidays. But you just never know, do ya? We were, of course, totally shocked and wondered why it had taken more than 15 years for her to tell us this. I wonder what stories will come out of all my children as time goes by? Thanks for your encouragement to probe.

michele

From VF, on Facebook: “I was fortunate to have wonderful kindergarten and grade 1 teachers. When Gr 2 looked like what you describe to be your experience, I “told” my Dad, who spoke to the teacher, and any other teacher thereafter who promoted pupil abuse, telling them they were not allowed to touch me (knowing him, he most likely promoted different methods but they probably stood their ground) – although I don’t ever remember it being obvious that I was “protected” because I was not shielded from teachers’ verbal abuses, I sometimes wonder if the other kids noticed that I didn’t get slapped, etc… Yep, those where not the best of times, but I’m so glad my Dad took action.”