[Extra Normandy photos at the bottom of this post.]

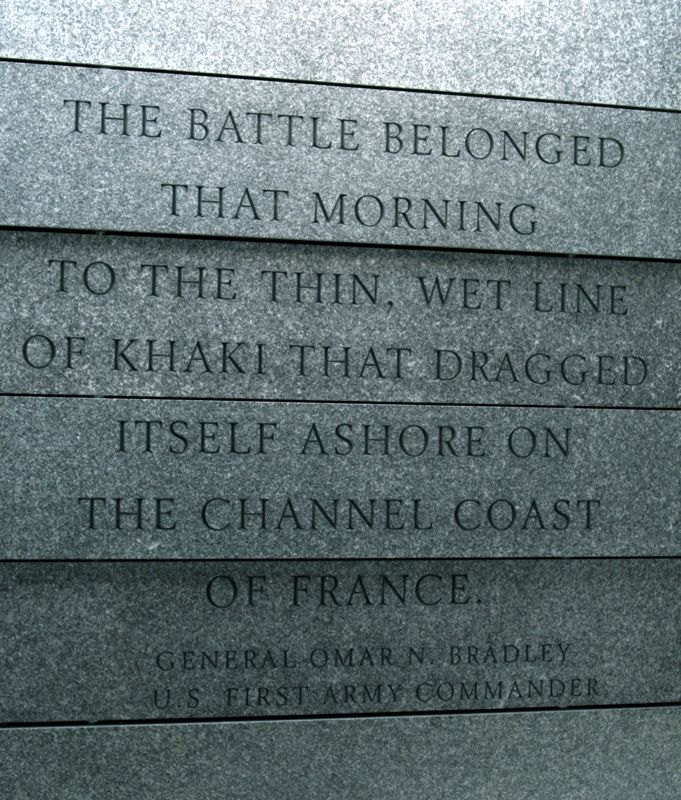

April 11, 2010. I wasn’t prepared for the sea of white crosses that spread across the horizon when I turned away from the desolate beauty of Normandy’s Omaha Beach and faced the American Cemetery where 9,387 white crosses and stars of David marked the graves of soldiers who fell during the D-Day landings of World War II. As we’d waited in line minutes before, I’d overheard a French schoolteacher explaining the significance of the site to her students. “It’s because of the men buried under these crosses,” she’d said, “that we speak French today—that we’re French at all. If these men hadn’t given their lives…” Her voice trailed off.

I wandered down row after row of crosses, minutes later, reading names and dates-of-death: Billy Tucker and John Tucker—bothers killed 11 days apart. Joseph Plotnick, a Jewish soldier. Archibald Cousins. Jeremy Smith. Anthony Scallia. So many names—so many crosses erected for unidentified soldiers “known but to God.” The words of a beloved student upon her return from a class trip to Normandy came back to mind. Her voice had been sharp with disapproval as she’d said, “It was all such a waste. All those men dead for nothing. People just need to get along, not wage wars against each other.”

Waste. The word felt sacrilegious in such a place, even though it was only in my mind. I stood over the remains of men whose deaths each signified a universe of loss for those who loved them… They were fathers, brothers, and sons who were so committed to something beyond themselves that they enlisted and died by the thousands to defend it. They had nothing to gain personally from risking everything on the beaches of Normandy. They simply had orders and the conviction that freedom for others was worth their own death, if that’s what it required.

As I stood in the American cemetery, my mind flashed back to the documentaries I’ve seen about the liberation of Europe that found its impetus on the beaches of France. The photos of stacked, emaciated bodies in concentration camps, of medical experiments that defied any sense of humanness. The terrified masses in so many countries who, though free, lived in horror and despair.

The lives of the men who crossed the Channel starting on June 6, 1944, were not wasted. Of this I’m sure. They were sacrificed. Waste is useless—sacrifice is noble, because it gives without measure for someone else’s good. Those lives were surrendered by the thousands, in service to a cause that had little bearing on the daily existence of 17-year old American boys. And yet they went. American, Canadian and British, they stepped out of those boats into the reddening tide and gave up their lives for strangers who might as well have been each one of us. As they waded through waters thick with their comrade’s corpses and faced the hail of artillery fire that mowed them down from the hills above the landing shores, they may have had only a vague notion of what their courage would achieve. But that notion—that selfless sense of duty—propelled them forward over mounds of fallen heroes and to the cliffs where snipers held their fate.

It’s called sacrifice. It’s called giving for the sake of giving, with no guarantee that it will change anything, but with the kind of ideals and valor that transcend self-preservation.

I lived in Germany. I lived where Hitler once reigned unchallenged and where the Allied Invasion, though it happened hundreds of miles away, toppled his Aryan ambitions and crushed his plans for global domination. Because of heroes like Joseph Plotnick and the Tucker brothers—because they sacrificed their futures to ensure ours—concentration camps were liberated after millions had already been starved, tortured and exterminated. Nations were returned to the hands of their own people. Minorities, the sick and the handicapped were given back their right to live as a maniacal dictator was halted and dethroned.

Yes, those French school kids have the fallen soldiers of Omaha Beach to thank for a country that is free. So do millions of Europeans who were neither strong enough nor many enough to fight for their own freedom. So, in a very real sense, do we.

I did fairly well with containing my emotion as I walked through the cemetery. Then I made my way toward the memorial, where a small ceremony seemed to be happening. When the National Anthem began to play through the speakers, every American within earshot turned and faced the flag, hand over heart, to honor the fallen. It wasn’t an act of national arrogance. Their tears and mine were an expression of our gratitude for those who gave so much, of awe for the courage that cost them their lives, and of honor for the sacrifice—yes, sacrifice—that made of their deaths a supreme act of valor. God bless the men and women in uniform who keep us safe and free. And may our government quickly realize that the “big stick” our soldiers represent is our last line of defense against our greatest foes.

Sacrifice, even to the death, used to be an integral part of our thinking and motivation. I want my life, too, to be defined by selflessness, and yet… Would I be willing to give up my own life for something that is morally just, even if it was of no benefit to me? I hope I would, but I don’t think we ever really show our mettle until we face the Arromanches cliffs in our own lives. All we can do until we’re truly tested is pray that the small sacrifices each of us make daily can be measured in terms of what they do for others rather than what we gain from them.

Remnants of the floating harbor in Arromanches.

Beautiful beaches that hold such horrific (and noble) history.

Children now play on the German bunkers atop the cliffs.

A scenic “Normand” village.

Streetlamps–I’m addicted.

The Bayeux cathedral by night.

wnpaul

I was touched by the words of the French school teacher you quoted. All of this is so distant and unreal to children growing up today. Even the Cold War and the Iron Curtain are meaningless to my children to whom Bratislava is a shopping paradise.

I have visited Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria several times in the past few years, and observing groups of high school students there who are overwhelmed by the horror of what happened has convinced me that we need places like the preserved camps, and the cemetaries in Normandy and elsewhere, to keep alive the determination of “Never again!”